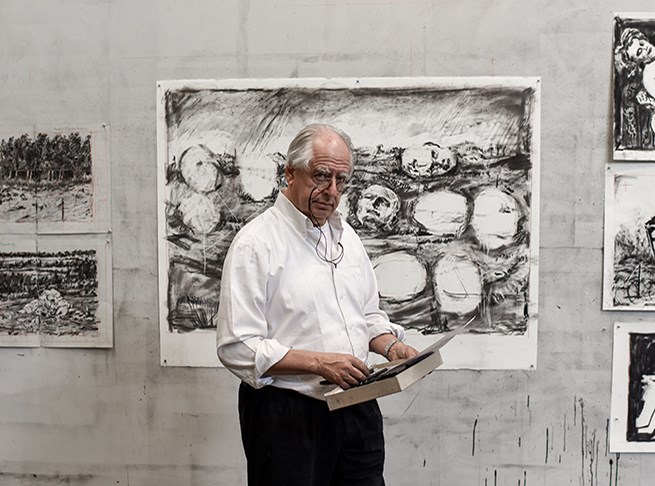

“Art is not a mirror to reflect the world, but a hammer with which to shape it.” This quote, often attributed to Bertolt Brecht, could very well have been said by William Kentridge, a South African artist born in 1955, whose work has consistently challenged and reshaped our understanding of art and society. His unique blend of mediums, from traditional drawing to animation and performance art, has not only broadened the scope of artistic expression but also provided a powerful commentary on history, memory, and identity. His parents were advocates who represented people marginalized by the apartheid system, and this early exposure to the socio-political landscape of South Africa had a profound impact on his work. This essay explores the evolution of Kentridge’s artistic expression, tracing his journey from his early exploration of personal narratives and memory, through his shift to multimedia and animation during his middle career, to his recent works that possibly involve large-scale installations or performance art.

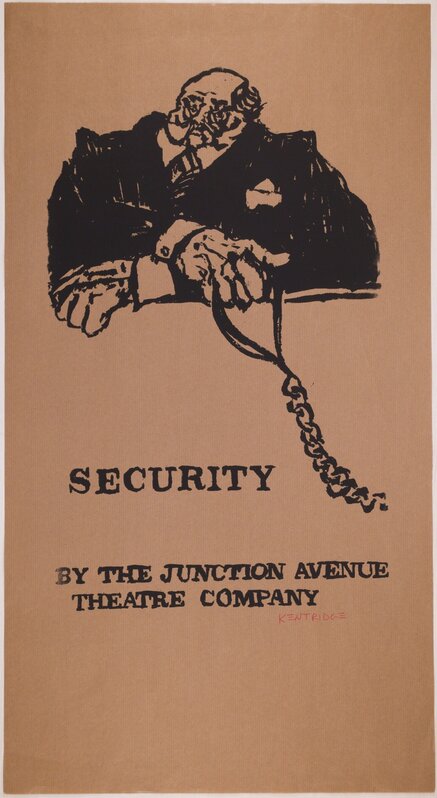

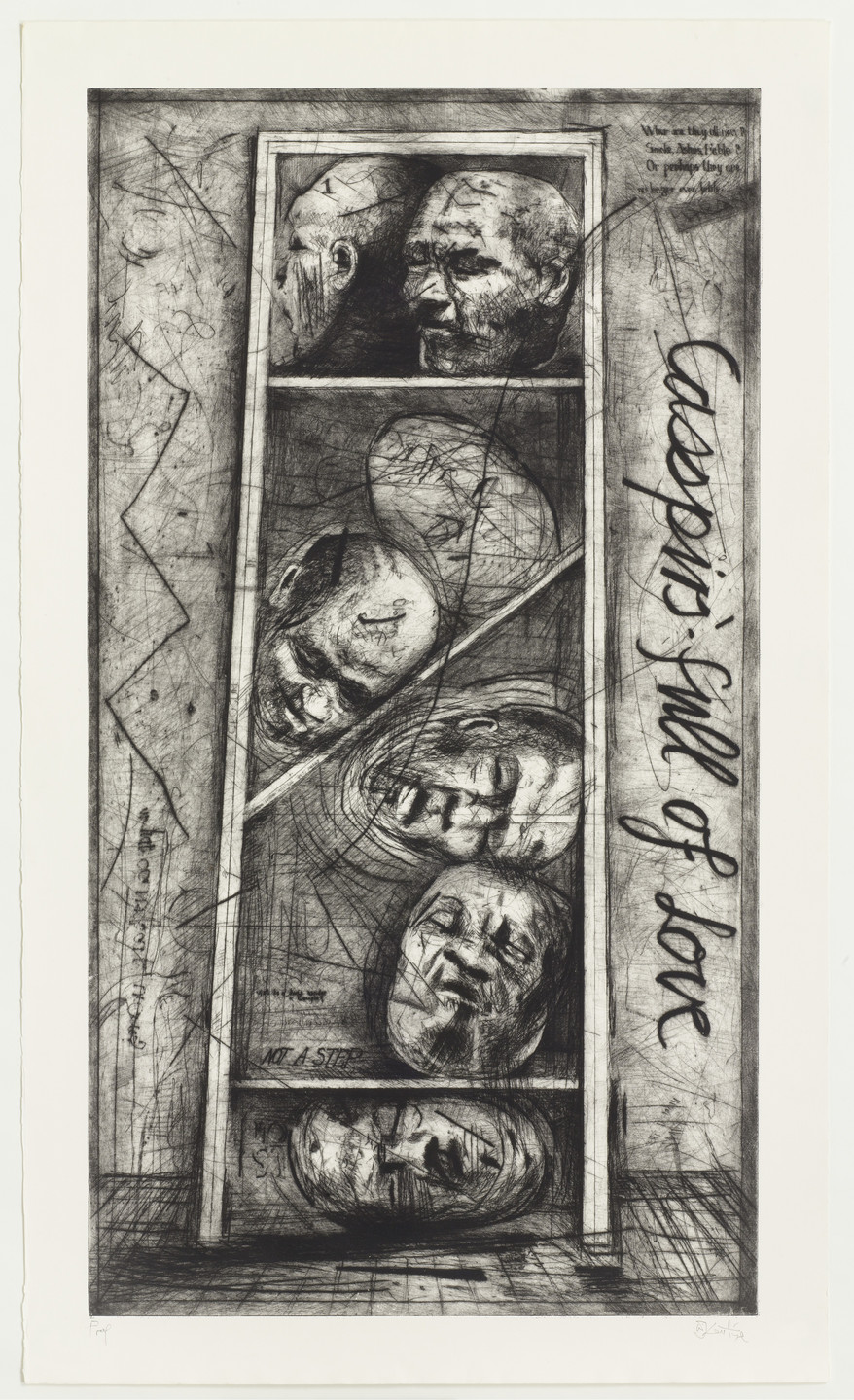

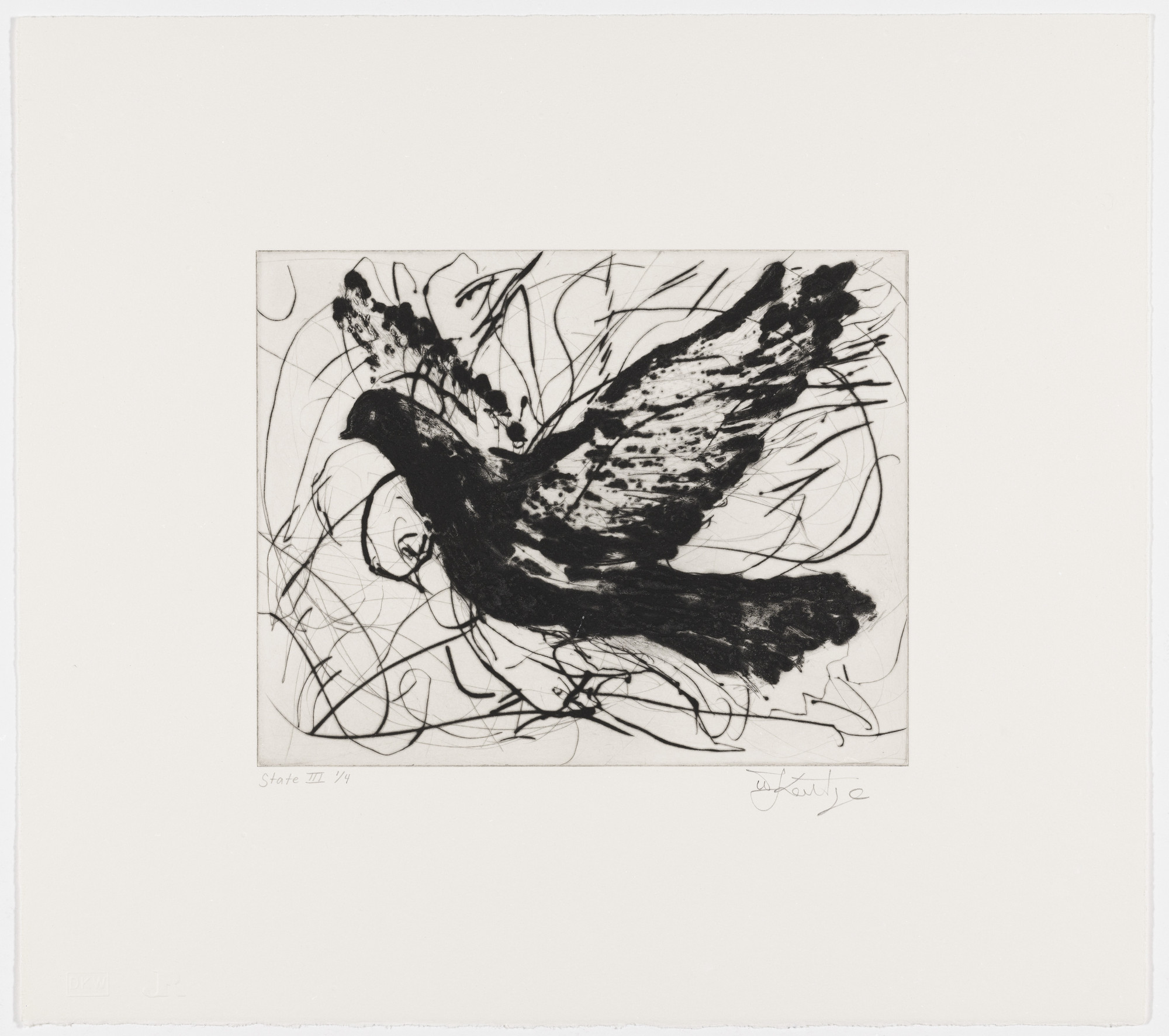

In his early career, Kentridge’s work was characterized by a strong focus on personal narratives and memory. He often used traditional drawing techniques to explore these themes, creating works that were deeply personal yet universally relatable. “Security” (1980), a screenprinted poster, showcases Kentridge’s initial exploration into themes of memory and personal narrative. It reflects the socio-political tensions of the time, offering a glimpse into the personal experiences and memories that shaped Kentridge’s early artistic vision. “Casspirs Full of Love” (1989), a print reflecting on the history and memory of apartheid, demonstrates Kentridge’s ability to use art as a tool for social commentary. It is a powerful testament to his early career focus on socio-political themes, and it marks the beginning of his transition towards more complex mediums and narratives.

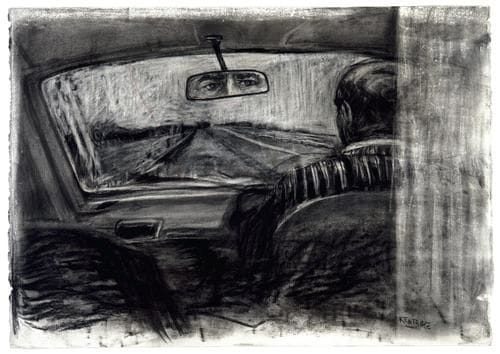

As Kentridge’s career progressed, he began to experiment with different mediums and techniques. His focus shifted from personal narratives to broader socio-political themes, marking the beginning of his middle career. “Felix in Exile” (1994) marks a significant shift to multimedia and animation in Kentridge’s career, providing commentary on displacement and identity. It reflects Kentridge’s evolving focus on socio-political themes and his innovative use of animation to convey complex narratives. “History of the Main Complaint” (1996) continues Kentridge’s political discourse through animated storytelling, addressing the complexities of apartheid. It demonstrates his ability to use art as a tool for social commentary, offering a critical examination of the socio-political landscape of South Africa during the apartheid era.

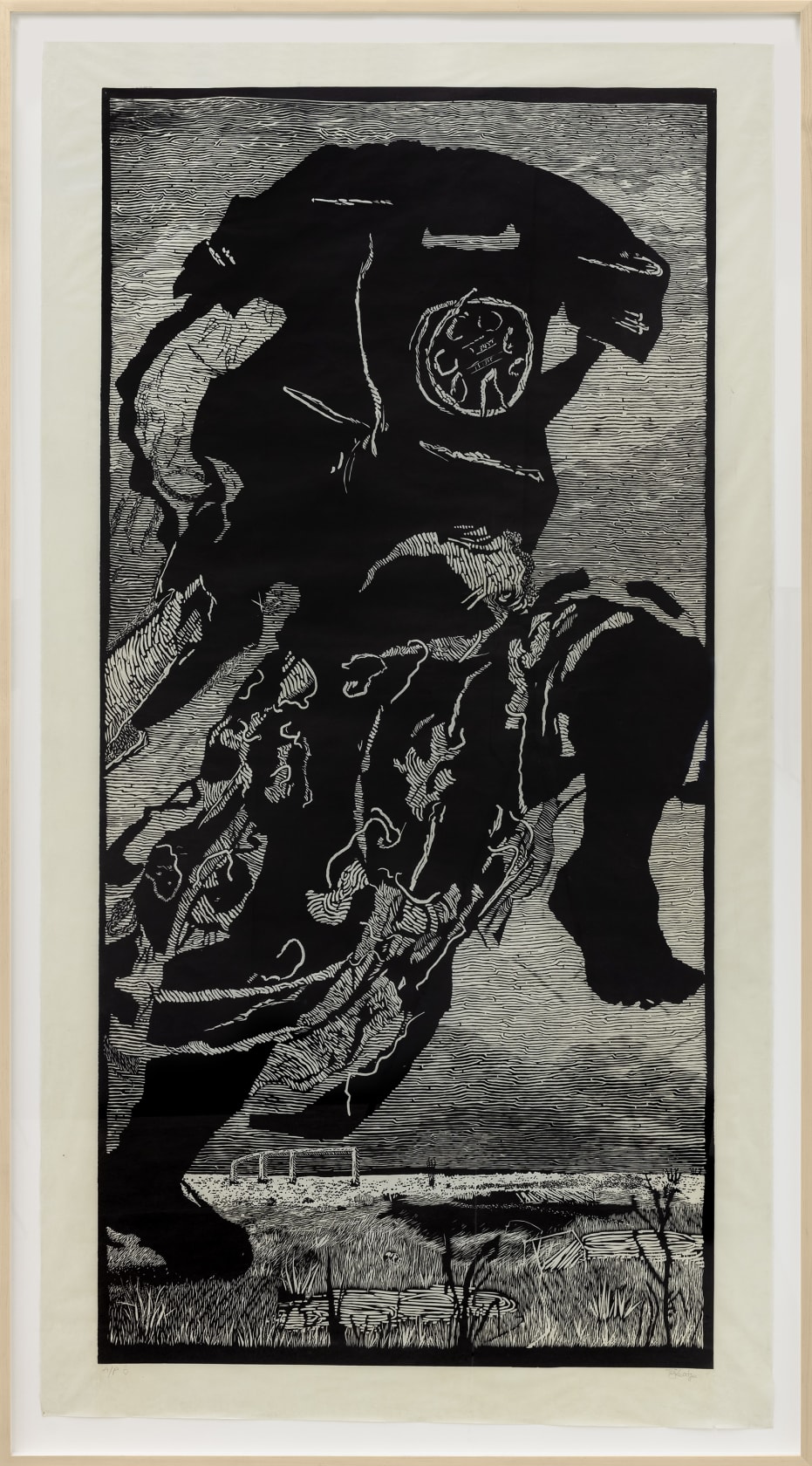

In his recent works, Kentridge has continued to evolve, possibly involving large-scale installations or performance art. His mature style is characterized by an interdisciplinary approach, blending contemporary socio-political themes with various artistic mediums. “Telephone Lady” (2000) represents Kentridge’s mature style, possibly involving large-scale installations or performance art. It reflects Kentridge’s continued exploration of contemporary socio-political themes through an interdisciplinary approach. “7 Fragments for Georges Méliès” (2003), an installation of seven film fragments, showcases Kentridge’s interdisciplinary work, blending contemporary socio-political themes with homage to early cinema. It demonstrates his innovative approach to storytelling and his ability to adapt and evolve, marking a significant milestone in his artistic journey.

This essay has traced the artistic journey of William Kentridge, from his early exploration of personal narratives and memory, through his shift to multimedia and animation during his middle career, to his recent works that possibly involve large-scale installations or performance art. Each phase of his career offers a unique perspective on his artistic evolution, reflecting the socio-political themes of his time and his innovative approach to art. Kentridge’s work holds significant implications for contemporary art. His innovative blend of mediums and his ability to adapt and evolve demonstrate the limitless possibilities of artistic expression. His exploration of socio-political themes through art provides a powerful commentary on history, memory, and identity, making his work not only aesthetically compelling but also intellectually stimulating. In the words of Kentridge himself, “In the end, it is never the object but the light on the object, the dust on the object.” This quote encapsulates the essence of Kentridge’s artistic journey – it is not just about the artwork itself, but the context, the themes, and the narratives that the artwork illuminates. As we reflect on Kentridge’s evolution as an artist, we are reminded of the transformative power of art and its ability to shed light on our understanding of the world. His work, whether it is a drawing, a print, an animation, or an installation, offers a unique perspective on history, memory, and identity, making it a compelling subject for this exhibition.